ASSESSMENT

2021 closes with a stabilized oil market in its fundamentals; however, there are still considerable uncertainties regarding the behavior of the world economy due to the Omicron variant of COVID-19. Gas and coal prices have experienced an extraordinary rise in industrialized economies, revealing an anticipated crisis of the so-called energy transition towards a «green economy».

After the failure of OPEC+ and the price war of March 2020, the producing countries grouped there, under the leadership of Saudi Arabia and Russia, were able to reach agreements and successfully deal with the unprecedented drop in oil demand and prices that were dramatically revealed in the second quarter of 2020. Since the extraordinary production cuts of 9.7 million barrels per day (MMBD) that came into effect in May of that year, prices have been slowly recovering, reflecting a stabilization of the market by regulating supply and draining inventories in the face of the fall and the slow recovery of world oil demand.

2020-2021 were years in which OPEC’s fundamental values and principles were reaffirmed: oil is a natural resource, and there must be an intervention in the oil market to regulate its production and reach a fair compensation for it. The policy of making OPEC+ production cuts more flexible and alleviating the domestic situation of producing countries has allowed the market to be supplied by the recovery of the economy and the demand, maintaining inventory levels at the average of the last five years.

The world economy continues to recover after the collapse of 2020, which was a consequence of massive restrictions and shutdowns resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout 2021, a slow recovery has been experienced, led by the major industrialized economies: the US, China, and Europe. However, successive variants of the virus, the most recent of which being Omicron, continue to cause travel restrictions in movement and economic activity, slowing its recovery.

The disparity between rich and poor countries in the access to and distribution of vaccines to combat COVID-19 has caused the different strains of the virus to mutate and appear as variants that, in any case, affect the population, even in countries with high levels of vaccination. On the other hand, as a result of the massive monetary resources injected into the U.S. and European economies, the phenomenon of inflation has risen, which, along with the issues in the supply chain and products, has caused difficulties in the normalization and growth of the world economy.

The U.S. and China have demonstrated their powerful economic and recovery strength. The Biden administration reversed the Trump administration’s denialist stance and has focused its government action on controlling the pandemic and recovering the economy; while China has shown its discipline and powerful production capacity, being the only economy that did not decline in 2020 and reflecting one of the highest growths in 2021. However, both superpowers are engaged in complex economic and political disputes that maintain important tensions and uncertainties in the recovery of the world economy.

The process of the economic recovery of the large industrialized economies, which are net importers of energy, have not had their energy needs met as a result of the rising prices of gas and, consequently, of the alternative for electrical and industrial use: coal.

Although the characteristics of the gas market are different from those of the oil market, they are highly dependent on the physical availability of infrastructure and are immature markets, lacking interconnection; their price is linked by the type of formula and the price of liquid fuels, their natural alternative. Therefore, the increase in oil prices, over $75 a barrel, in addition to the supply restrictions in Europe, via gas pipelines, and in Asia, via liquefied natural gas, has caused an increase in its prices of 600%, with a peak of 940% on December 21, which has become a severe economic problem for the demanding countries, particularly during the winter in the Northern Hemisphere — annual inflation[3] in the energy sector in the Eurozone as of November was 27.5%. At the same time, it has caused a price increase in the North American gas market, which has led to significant volumes being exported via LNG.

Given the absence and cost of gas and liquid fuels, large consumers have turned to coal, increasing its price. The most emblematic case of this phenomenon has been China.

The rise in energy prices in Europe and Asia demonstrates, on the other hand, the real problems of the so-called «energy transition» towards a green economy that foregoes fossil fuels. The industrialized world is far from being able to part ways with these fuels. Neither renewable energies, such as wind and solar, nor atomic energy are capable of becoming an alternative to the consumption of oil, liquid fuels, gas, or even coal.

At its last meeting on December 2, OPEC+ missed the opportunity of taking strategic action by releasing more oil volumes as part of its easing policy to level prices in favor of the recovery of the world economy and the oil demand, as well as to remain as the fair-price energy source necessary for economic development.

OPEC+ must take a stance in favor of the environment, demand the rationalization of oil consumption — as a conservationist policy of the natural resource — to counteract the anti-fossil energy positions that have gained ground in industrialized countries, especially in Europe and the USA, in favor of other energy sources, including nuclear energy, thanks to the political pressure of public opinion as well as the powerful economic lobby of investment fund and producers of renewable and nuclear energy.

Looking ahead to 2022, the expectation is focused on the full recovery of the global economy and oil demand to the pre-pandemic levels of 2019, as well as on monitoring oil market fundamentals to maintain the stabilization achieved in 2021. The aspect that will have the greatest impact on the oil market and on OPEC, in particular, will be the favorable results of the negotiations on the nuclear agreement between the US and Iran. This will allow the lifting of US sanctions on Iranian oil production and the eventual recovery of the Persian country’s production to 4 million barrels of oil per day — its quota within OPEC+ before the sanctions– which will not only guarantee oil supply to China and Europe but will also cause a realignment of forces within the organization, disputing the Saudi hegemony and politically balancing OPEC.

PRICE

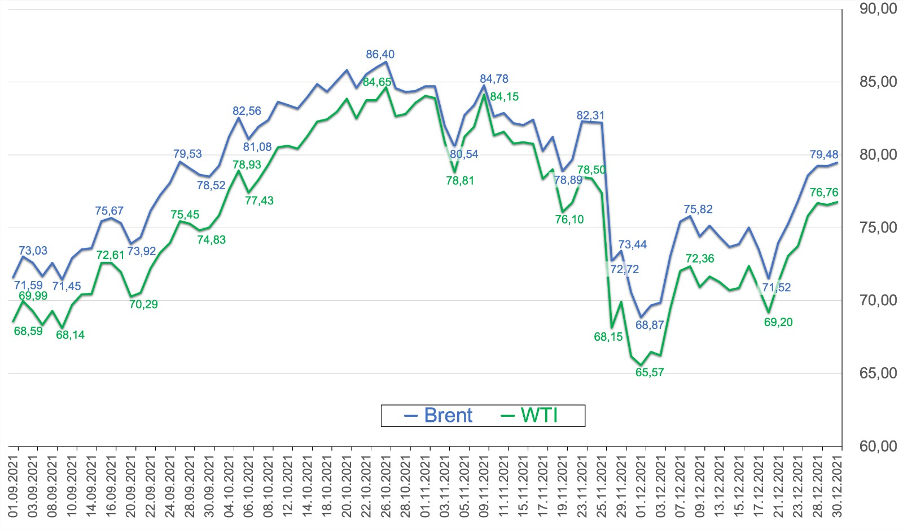

On December 30, at the close of European markets, Brent (ICE Future Europe) and WTI (NYMEX) crude oil markers continued to rise, trading at $79.48 and US$76.76 per barrel, respectively; an increase of more than $10 for both markers since December 02. Oil prices close 2021 at the $80 a barrel threshold, regaining the trend of the September-October period where markers traded above $80 a barrel, before the drop on November 26 when the detection of the new variant of COVID-19, Omicron, was announced[1].

BRENT AND WTI CRUDE OIL PRICES

(September – December 2021)

The world oil market was heavily impacted by the announcement of the Omicron detection, dropping nearly $10 a barrel. Then, on November 30, the oil price traded at its lowest level in four months, falling by more than 5% that day, after Moderna laboratory CEO Stephane Bancel further alarmed the market by stating that [2] existing vaccines were expected to «be less effective» against the Omicron variant.

The impact of Omicron’s appearance on oil prices coincided with the unprecedented announcement [3] by US President Joe Biden on November 23 that the major oil consumers (China, South Korea, India, Japan, and the UK) had agreed to a joint release of their strategic oil reserves as a result of «diplomatic work» to «reduce prices and address supply shortages». The US president took the first step, informing that his country will «release» 50 million barrels of its strategic reserves; India announced that they will release 5 million barrels, while the United Kingdom will release 1.5 million barrels.

These two elements combined halted the rise in the price of oil, which was expected to close the last four months of the year above $80 per barrel and caused it to fall by more than $13 per barrel between November 24 and December 01, bringing the price of crude oil to below $69 (Brent) and $66 (WTI).

It is in these circumstances, at a time when oil prices had plummeted by more than 20% between November 24 and December 01, that OPEC+, at its 23rd Ministerial Meeting[4] held on December 02, announced the upward adjustment of 400 thousand barrels per day for January 2022, ratifying its policy of flexibilization of the production cut, in accordance with the adjustment mechanism schedule approved last July 18. This decision had an immediate impact, causing the price of oil to climb more than $3 in less than two hours, recovering 7% of its value. Between December 05 and December 07, the Brent and WTI markers returned to trade above $70 a barrel.

The impact of the OPEC+ decision was reinforced on December 06 when, from the USA, the health authorities reported that the first information they had obtained on the Omicron variant «is encouraging», lowering the alarm initially generated. Prices continued to rise to trade above $75 (Brent) and $72 (WTI) until December 22, when they spiked $4 in the last week of the year, topping $79 and $76.

Since the decision taken at the 23rd OPEC+ meeting on December 02, the price of Brent and WTI recovered by more than $10 per barrel, supported by weather forecasts of a colder than expected winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Thus, amid the uncertainties that continue to affect the psychology of the oil market and the prospects for the recovery of the world economy, the price of oil resumes the trend of a sustained recovery in its value, which during this year allowed a growth of 60% ($30) concerning its prices at the close of 2020, with prices in October and November above $80 a barrel, which exceeded, by more than 90% (more than $40) those of the previous year.

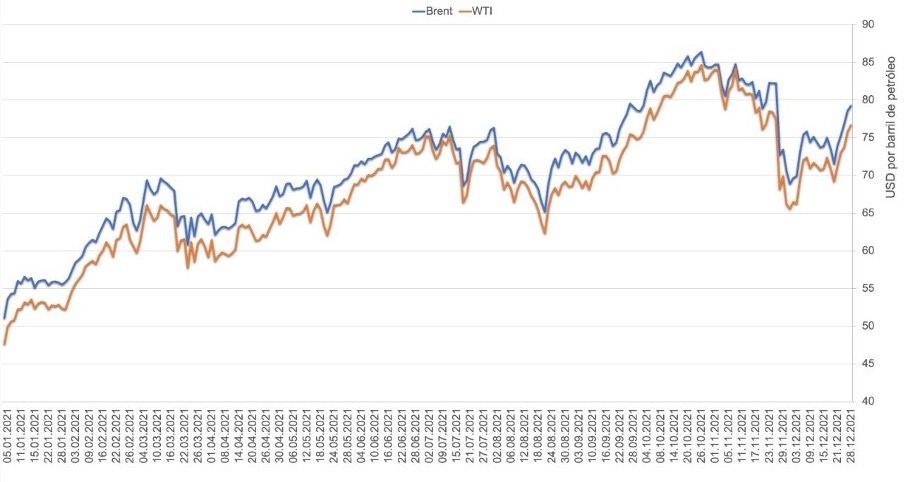

Throughout 2021, the oil market has experienced a stabilization process mainly due to the OPEC+ cuts policy, the vaccination process against COVID-19 in the world, the recovery of the world economy and oil demand, as well as the draining of oil inventories, all of which has been reflected in the recovery of prices, which aim to remain stable above $80 per barrel by 2022.

BRENT AND WTI CRUDE OIL PRICES

(January – December 2021)

The current Brent and WTI prices reflect an increase of 210% and 305%, respectively, over their April 2020 price and 20% and 25%, respectively, over their December 2019 one, a clear indication of the recovery of global oil demand and the stabilization of the market after the 2020 collapse due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although uncertainty factors continue to affect the prospects for recovery of the world economy and oil demand, such as the emergence of the COVID-19 Omicron variant, problems in the supply chain of inputs and outputs, the phenomenon of inflation, and the extraordinary increase in the price of gas and coal in Europe and Asia, all estimates and analyses point to the recovery of the economy and demand being maintained throughout 2022, which will allow OPEC+ to continue with the policy of flexible production cuts, keeping the market stable and the prices at comfortable levels.

In their December monthly reports, both OPEC[5] and the International Energy Agency[6] (IEA) did not consider the COVID-19 Omicron variant to be a factor that would slow down the recovery of oil demand.

Despite these considerations, the exponential increase of COVID-19 and its variant Omicron, as of December 29, with 19.25 million new cases[7] (5 million more than the new cases detected in November), has caused the reactivation of measures to restrict internal and external mobility in Europe and Asia, placing an end-of-year brake on the expectations of accelerating the economic recovery gained during 2021.

Meanwhile, among the oil-producing countries, grouped in OPEC+, a more cautious stance prevails regarding the situation of the world economy and oil demand, as expressed by the Saudi Arabian Minister of Energy, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, when, before the 22nd Ministerial Meeting, said that the crisis caused by the pandemic was -to a certain extent- contained, but that it was not over. «We have to be vigilant, not take things for granted» [8].

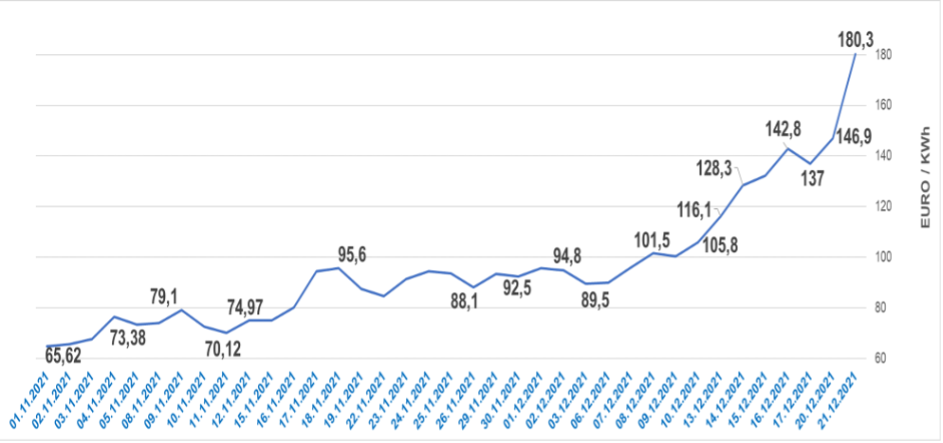

Gas prices in Europe

One element that continues to impact the energy market, especially in Europe and Asia, has been the steady increase in gas prices, linked both to the cost of oil and liquid fuels, as well as to geopolitical tensions -especially in Europe- and unsatisfied energy needs in the industrialized economies of Asia.

Gas prices have soared to historic levels since September of this year, with increases of more than 500% in the Asia-Pacific region and 900% in Europe, where the prices have been over 100 euros per megawatt-hour (MWh) since December 08, with peaks of 180 euros, dragging up coal prices with it, given the insufficient supplies and the cost of oil to meet the energy requirements for the recovery of the world economy.

In Europe, gas storage and supplies of «alternative energy» and nuclear energy have proven insufficient to cope with the shortage of Russian gas supplies and the threat of its suspension due to geopolitical tensions with this country. This clearly reveals the still high dependence on fossil fuels. A hard test for the «energy transition» that has forced the EU authorities to take a step backward -and a reasonable one- by considering gas within the «transitional» or «green» energies, in a way of considering this fossil fuel as a transition fuel[09][10], over the use of coal and nuclear as energy sources.

GAS PRICE FOR EUROPE

(November – December 21, 2021)

The cold snap from the Arctic, which has affected northern European countries, brought forward the use of insufficient gas reserves [11] -below the 75% of demand set by the EU as a strategic target- and had an upward impact on gas prices at the end of November and in December.

In addition to this, geopolitical tensions between Europe, the US, and Russia are putting Russian gas supplies to the continent under pressure. In November, gas prices in Europe rose again, this time by 18%, due to the decision of the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur), the German regulator, to suspend [12] the certification procedure for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, the second branch of the project to supply Russian gas to Europe through Germany, crossing the Baltic Sea.

Already in December, the new German Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, warned Russia that «there will be no gas pipeline (Nord Stream 2)» as long as Moscow «does not abandon» its position on Ukraine [13]. In the face of US and NATO pressure, Russian President Vladimir Putin warned that Moscow «is prepared» to respond with «military and technical measures» to the actions being taken on the borders of his country [14], while denouncing that Germany was reselling Russian gas to Poland and Ukraine, for which reason it decided to divert gas supplies through the Yamal-Europe pipeline in the opposite direction (to the east, towards Poland).

All of the above led the price of Dutch TTF Gas Future, the gas marker for the European market, to once again exceed 90 euros per Megawatt Hour (MWh), which had not happened since October 20, and to settle at over 100 euros since December 8, reaching the 180-euro barrier on December 21, historic levels recorded in recent days.

At the close of December 28, the Dutch TTF traded at 106.6/WWh euros, remaining stable for the last 48 hours, up 12 euro since December 01, increasing its value by 13% in the month. For the second half of 2021, the Dutch TTF price has risen by 190% and by 490% since the beginning of the year. This is in addition to the reiteration of the Belarusian government’s warning not to allow Russian gas to enter Europe if the EU applies new sanctions against the country.

PRODUCTION

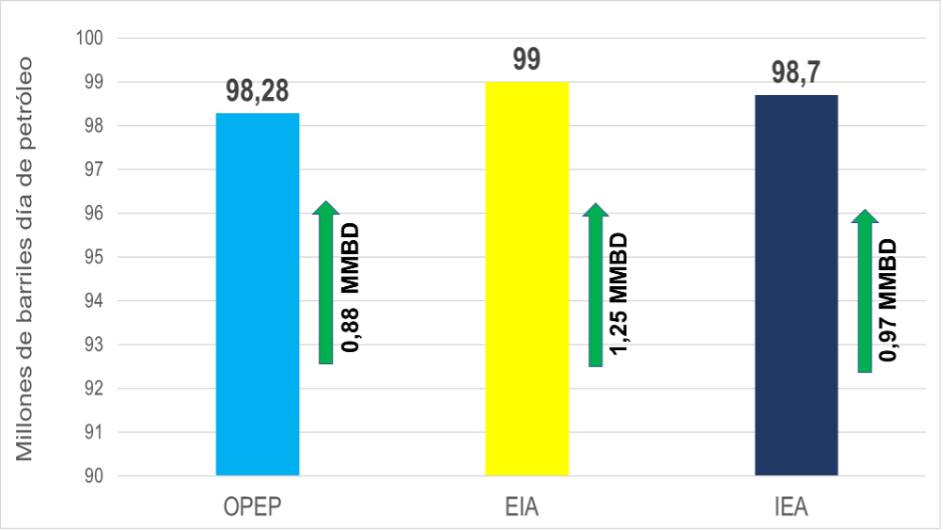

World production of oil, condensates, LNG, and unconventional liquids (PCL) continues to increase gradually, mainly due to OPEC+’s policy of flexible cuts and the entry of volumes from the US and other producers, stimulated by the recovery of oil prices.

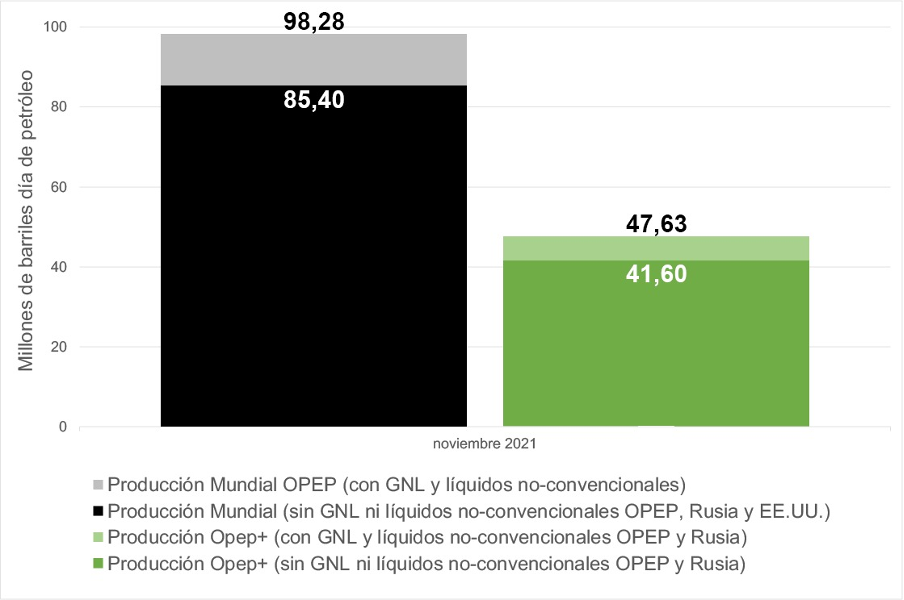

According to data from OPEC’s latest Monthly Oil Market Report [15] (MOMR) on December 13, world LCP production in November stood at 98.28 MMBD, representing a monthly increase of 0.88 MMBD. On the other hand, the Energy Information Administration(EIA) [16] estimates that PCL production in November was at 99 MMBD (1.25 MMBD monthly increase), while the IEA put it at 98.7 MMBD (970 MBD).

WORLD PRODUCTION

of crude oil, condensates, LNG, and unconventional liquids

(November 2021)

World oil production

If we separate the volumes of condensate, LNG, and unconventional liquids in the U.S., Russia, and OPEC from world PCL production, world oil production stands at 85.4 MMBD in November, according to both OPEC and EIA data, as well as data from the Russian Ministry of Energy.

November oil production shows a monthly increase of 1 MMBD, mainly due to OPEC+ easing and a 150 MBD recovery in US production.

WORLD OIL PRODUCTION

(November 2021)

In 2021, world oil production responded primarily to the production cuts agreed by OPEC+ in April 2020, as well as the production flexibilization mechanisms agreed last July 18.

Since May 2020, when the OPEC+ adjustment began by withdrawing 9.7 MMBD from the market, and U.S. production fell by 3 MMBD, OPEC data shows a 9.1 MMBD increase in global oil supply, while the EIA numbers do so by 10.9 MMBD.

In 2021, OPEC+ eased its production cut by 3.94 MMBD, while U.S. production saw a 600 MBD increase in output.

Thus, by 2021, adding OPEC+, the US, and other producers’ production, world oil supply had an annual increase between 1.5 and 1.8 MMBD, according to OPEC, EIA, and IEA data.

By 2022, the IEA forecasts an increase of 6.4 MMBD in world production, similar to the projection that can be made with OPEC data, with a supply close to 102 MMBD. For its part, the EIA projections for next year are 101 MMBD, forecasting an annual growth of 5.3 MMBD.

OPEC+ production

By November 2021, OPEC+ production stood at 41.6 MMBD, following the 400 MBD increase in its production quota. However, following the November and December production adjustment, the year will close with an OPEC+ supply increase of 5.94 MMBD, a 61% easing from the original 9.7 MMBD cut initiated on May 01, 2020.

By January 2022, the agreed adjustment of 400 MBD will be applied, leaving the production cut at 3,359 and the group’s quota at 38,741 MMBD (excluding production from Mexico, Iran, Libya, and Venezuela).

The production adjustment agreement will be in effect until December 2022, so, according to the agreement, the same 400- MBD-per-month flexibility scheme will continue to be applied until September or until OPEC+ has returned to the market the totality of the adjusted volume in May 2020.

Of the 400 MBD that OPEC+ will recover for its production quota in December, 205 MBD (51.25%) corresponds to the Persian Gulf monarchies (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and UAE) and Iraq, whereas Saudi Arabia will increase its quota by 105 MBD. Russia, like Saudi Arabia, will increase its production by 105 MBD. Saudi Arabia and Russia account for 52.5% of the production increase agreed for December, while the remaining 17 OPEC+ countries will split 47.5% of the increase among themselves.

For 2022, OPEC+ is expected to continue the monthly adjustment mechanism through September, until the remaining 3.759 MMBD of the May 2020 adjustment of 9.9 MMBD is released, although the agreement is in place until December 31 next year. In turn, as of May 01, 2022, an adjustment of 1.632 MMBD will be made to the production base of OPEC+ countries, bringing it to 43.732 MMBD, where Saudi Arabia and Russia will each rise to 11.5 MMBD (an increase of 500 MBD), while the UAE achieved a new base quota by 3.5 MMBD (an increase of 332 MBD).

This modification of quotas within OPEC+ will be made at the expense of other countries that cannot cover their base quota, as in the case of Venezuela, whose quota is equivalent to 11% of the organization’s production, but whose current production represents only 2.3%.

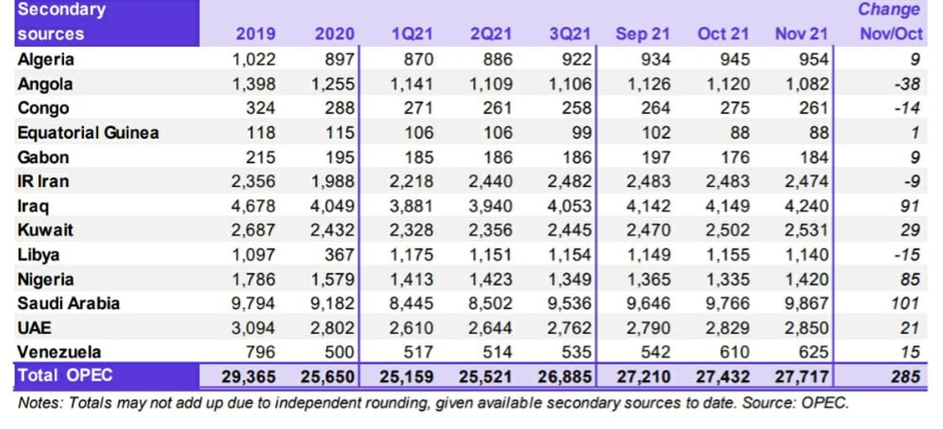

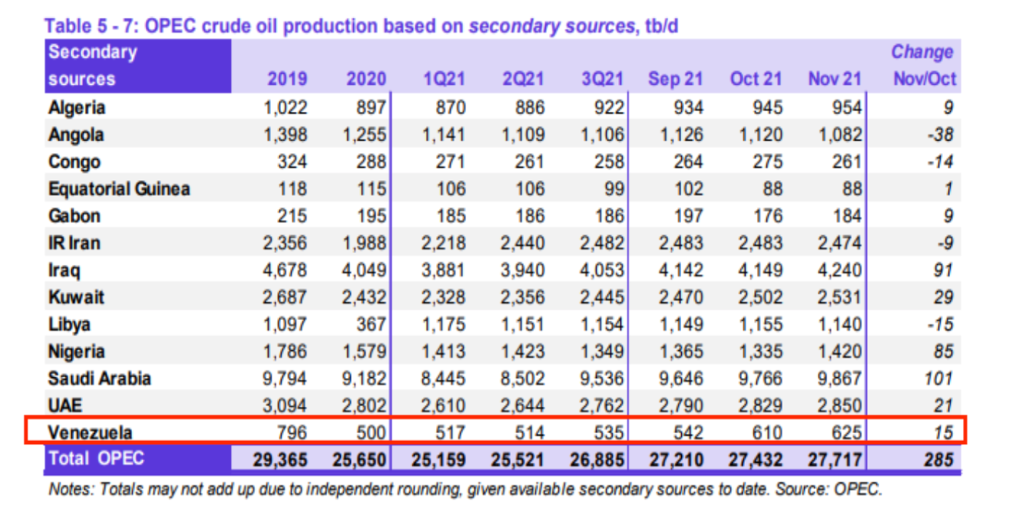

OPEC Production

OPEC Production According to MOMR data, member countries’ oil production as of November was 27.72 MMBD -the highest level in a year and a half as a result of the easing of their production.

OPEC COUNTRIES’ PRODUCTION

(November 2021)

Saudi Arabia along with the Persian Gulf countries (excluding Iran) totaled a production of 19,488 MMBD in October, corresponding to 70.3% of OPEC production, of which 9.87 MMBD corresponded to Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, African countries (excluding Libya) presented a production of 3.99 MMBD in October, 14.4% of OPEC production. Meanwhile, Iran, Libya, and Venezuela -the three OPEC countries exempt from production cuts- presented in October a combined production of 4.24 MMBD, of which 2.48 MMBD (58.5%) corresponds to Iran and 1.14 MMBD to Libya, while Venezuela’s production continues to stagnate at 625,000 barrels of oil per day.

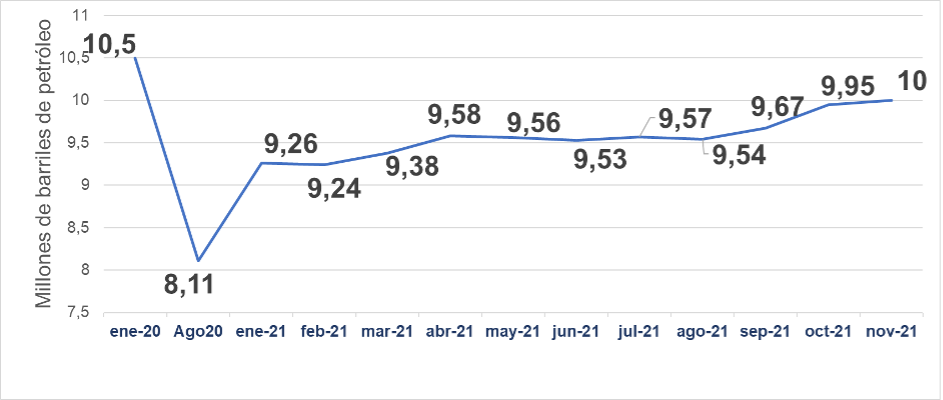

Russia

According to data published by the Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation, the country’s oil production in November stood at 10 MMBD, representing 24% of OPEC+ production.

RUSSIA’S OIL PRODUCTION

(January 2020- November 2021)

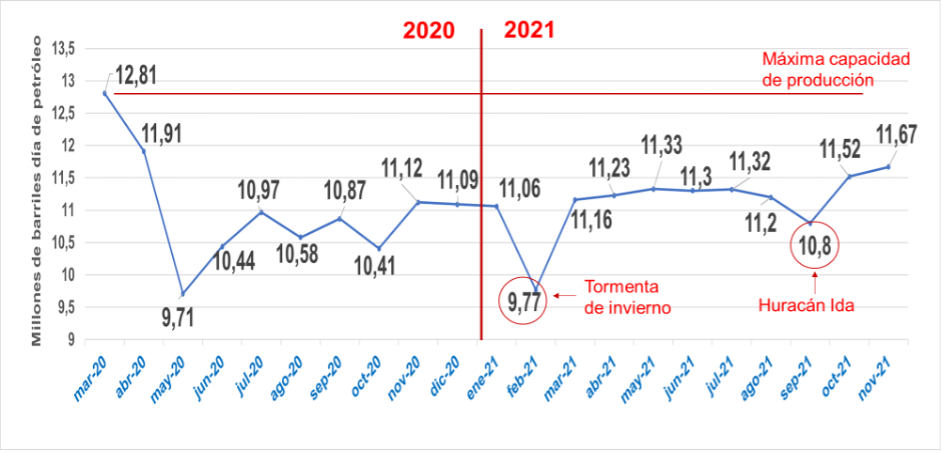

USA

US oil production continues to increase, showing a clear recovery during the year, after the 3 MMBD drop resulting from the 2020 oil market collapse.

The latest EIA report[17], released on December 29, puts US production at 11.8 MMBD, 200 MBD higher than the previous week and 100 MBD above production in the first half of December. Earlier, in November, the EIA reported production of 11.67 MMBD (a monthly increase of 150 MBD), its highest record since April 2020, showing a trend that keeps the US as the world’s largest oil producer.

US production has been stimulated both by the increase in world oil prices -which has allowed Shale oil producers to pay debts and dividends-, the recovery of the economy, as well as by the power of large US oil transnationals capable of reversing even President Joe Biden’s own executive orders and his «green economy» policy.

The US government, burdened by the needs of the economy, rising fuel prices, and inflation, is demanding and pressuring OPEC+ producers to increase their oil supply while pointing out that the increase in oil production in the US -local production- does not translate into a reduction in fuel costs for its domestic market.

The US President, in a statement [19] on November 23 and at a press conference the following day, criticized the «anti-competitive practices» of oil corporations, which would be preventing the US consumer from «benefiting» from the decrease in oil prices. «There is growing evidence that falling oil prices are not translating into lower prices at the pump,» Biden denounced.

The increase in US oil production exceeds the Department of Energy (DOE) Secretary’s own 2021 estimates, as well as the forecasts of 11.2 MMBD, and the projections made by the EIA in the November 09 and December 07 monthly reports.

U.S. OIL PRODUCTION *

(March 2020 – November 2021)

Source: Own elaboration with data from the EIA STEO of December 7, 2021.

The increase in US oil production goes against President Joe Biden’s policy of reducing the production and consumption of fossil fuels to contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions into the environment and to comply with the commitments of the Paris Agreement [19], one of his banners during the election campaign, which together with the «green economy» [20] won him the support of important young sectors of the Democratic Party.

The White House’s promise not to stimulate oil production by suspending federal aid and production subsidies, denying new federal land grants and permits for oil production, preventing the expansion of oil production into environmentally sensitive or protected areas, as well as revoking licenses and permits for infrastructure development to increase oil production, have clashed with the powerful interests of US oil transnationals and the imperatives of post-COVID economic recovery. In its strategic objective of maintaining its position as the world’s leading economic power and slowing China’s advance, energy self-sufficiency becomes an imperative, a fundamental advantage over its closest competitors: China and the rest of the Asian economies and Europe, all of which are dependent on energy imports.

The energy transition and the displacement of fossil fuels in the US, as well as in China, Asia, and Europe, are encountering the reality of the strategic interests of power and the needs of the industrialized countries, whose lifestyle and consumption patterns are the world’s major energy consumers.

This can be seen in the decision [21] that the White House was forced to make on November 17, when the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the agency in charge of authorizing and awarding bids in the federal waters of the Gulf of Mexico, was forced to sell the lease of Lot 257 (1.7 million acres with estimated reserves of 48 billion barrels of oil) to ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Shell, and 29 other companies, for a value of $191.7 million, after a June 15 ruling by Louisiana federal judge Terry Doughty revoked [22] Executive Order 14.008 [23] signed by the US president on January 27, which had suspended new oil and natural gas licenses on public lands and offshore waters.

ECONOMY

The year 2021 has been marked by a frank recovery of the world economy, led by the industrialized economies, particularly the US, China, Asia, and Europe.

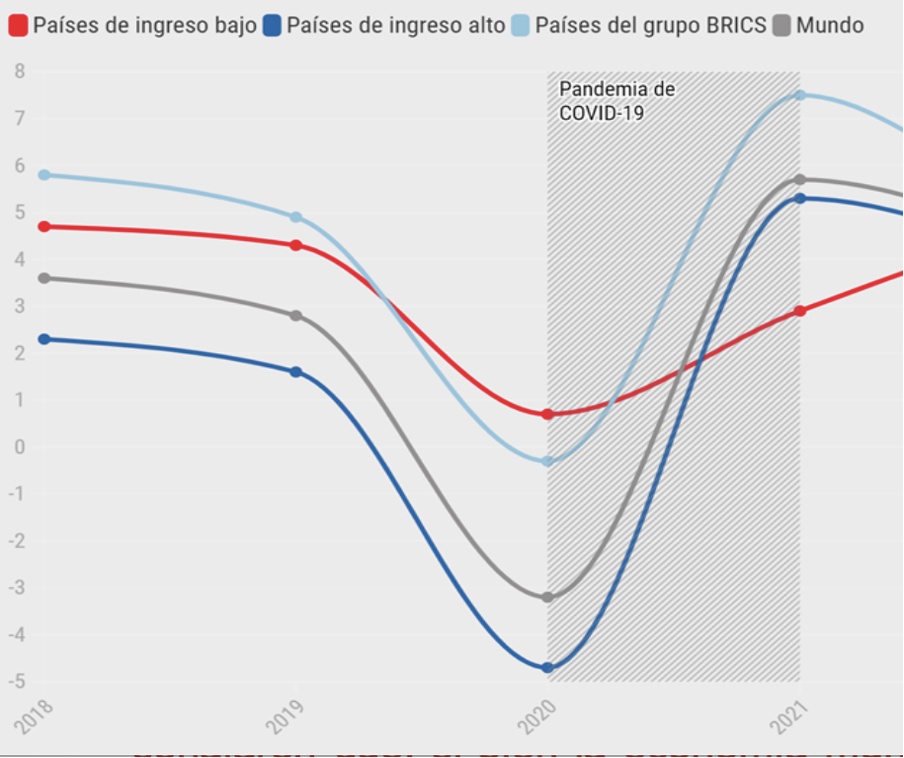

According to the latest projections of OPEC, the IMF [24], the OECD [25] and ECLAC [26], the world economy has experienced a growth of between 5.5% and 5.9%, where the US shows a growth of 5.5%, China of 8%, the UK 6.9% and 5% in the Eurozone in Europe; while Japan, India, and Russia show growth of 2%, 8.8%, and 4%, respectively, and Latin America will grow by 6%. Sub-Saharan Africa is the region with the lowest growth and economic recovery this year, with 3.8%. The world economy has been able to overcome the 3.1% decline in 2020, and the IMF projects in its latest report that the world economy will grow 6.0% in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022. However, according to the World Bank, this recovery has been marked by inequality; according to its «Economic Outlook», [27] there remains a very large gap in economic recovery between high-income economies and low and middle-income economies.

INEQUALITY IN THE RECOVERY

OF THE WORLD ECONOMY

GDP (2018-2021)

The June edition of the WB’s World Economic Outlook report notes that while the global economy will grow by 5.6% in 2021 (the fastest post-recession pace in 80 years), the recovery will be uneven. Low-income economies are currently projected to grow by only 2.9% in 2021, the slowest growth in 20 years, relative to 2020, in part due to the slow pace of vaccination.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not ceased to have an impact on the world population and returns with its variants -Omicron being the most recent one- affecting even industrialized countries, despite having advanced massive vaccination programs among their population. The emergence of the different mutations of the coronavirus occurs in those regions and populations of poorer countries where there has not been massive access to vaccines against COVID-19.

With more than 284 million cases and almost 5.5 million deaths, COVID-19 continues to cause disruptions and restrictions to air and land mobility, trade, and the economy, especially in Europe; although there is consensus among the scientific community and government agencies that the new variant of the virus, Omicron, is not as lethal or severe as the other variants of COVID-19, even if its transmission is faster.

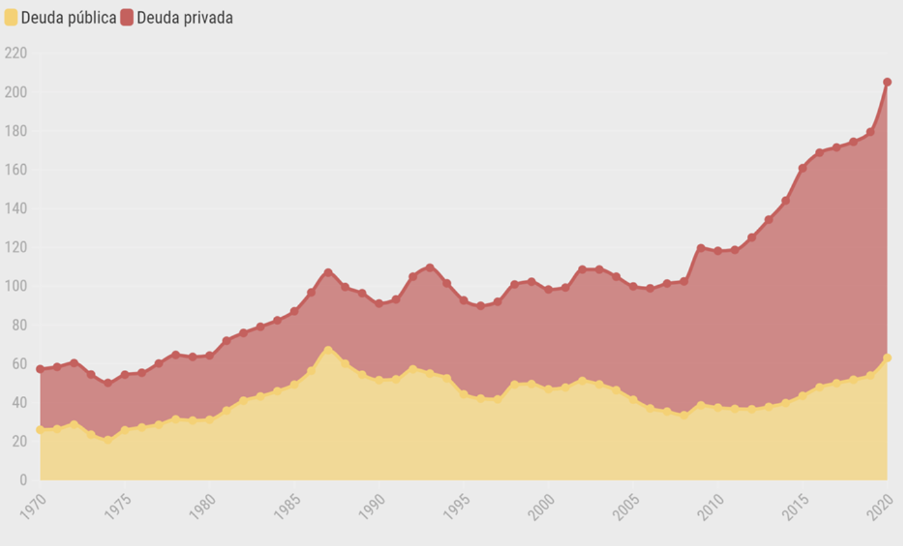

Additionally, the world economy must now confront problems stemming from the collapse of 2020: inflation, disruption of supply chains, and debt. As a result of the massive monetary bailouts to the economies of Europe and the US, where subsidies, loans, and grant packages totaling more than $6 trillion ($4.1 trillion in the US and $2.3 trillion in Europe) were injected, the phenomenon of inflation has occurred in the major industrialized economies. The Bureau of Labor Statistics [28] published that annual inflation for November in the US was at 6.8% – the highest rate in 39 years – whereas in November 2020 it was at 1.2%. In turn, Eurostat [29] reported that, for the same month, EU inflation was 4.9%, 0.5 points higher than the previous month; while in China, it was 2.3% annualized, with a variation of 0.8 points (higher) from October, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China [30].

The IMF reported in a statement [31] that the sectors that have had the greatest impact on inflationary growth within the industrialized economies are energy and food, which are expected to maintain their impact on inflationary growth until the end of 2022.

For its part, the OECD in its December «Economic Outlook» report is «cautiously optimistic» regarding the performance of the world economy (economy, wages, employment, and trade), estimating that 2021 will close with a growth of 5.6%, but coinciding with the World Bank that it will be in an unbalanced way, with a marked difference in the recovery among the advanced economies themselves, which is reflected in health, supply constraints, erroneous policy decisions, and inflation. The report points out that the CPI for food and energy continues to increase in 2021. Likewise, it warns that the labor market is in a situation of imbalance, where many people are unable to find employment, which is reflected in the employment rate in the active population, which has decreased.

The OECD points out [32] that the recovery of the demand for goods has been met with slower recovery in the production chain, causing a shortage in supply, creating a bottleneck in the production and supply chain. On the other hand, while the US has a labor shortage and needs to bring more people into the labor market, Europe needs to create more jobs and increase employment growth.

Inflationary «pressure» encompassed all economies, where inflation in 2021 is well above pre-pandemic levels. Both organizations agree that among the factors most influencing inflationary pressures have been the disruption of the food supply chain and the rising cost of energy, oil, gas, and coal. Debt burdens in emerging markets and developing economies have increased during the pandemic. The challenge worsens in low-income countries: half of them were in a critical situation caused by over-indebtedness or at high risk of being so before the onset of COVID-19. This comes after a decade that has seen the fastest, largest, and broadest expansion of debt levels worldwide, according to the Global Economic Prospects report.

DEBT GROWTH

IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

As policymakers in emerging markets and developing economies seek to move from pandemic response to recovery, they will need to be careful not to prematurely withdraw fiscal support and seek to increase the efficiency of public spending, while balancing the need for debt sustainability. However, the debt burden will be felt long after the virus disappears, when debt servicing costs rise, slowing recovery and hampering efforts to address other development challenges, including climate change.

There is more to debt than meets the eye, according to the findings of the World Bank’s «Debt Transparency in Developing Countries» report [33]. This is because debt reporting is not a very simple exercise. Global debt monitoring today relies on a combination of databases with different standards and definitions. These databases have large gaps: the latest World Bank report shows that publicly available records on the debt stock of low-income countries result in variations that can reach up to 30% of a country’s GDP, due to divergences in definitions and standards in local and international databases.

DEMAND

World oil demand in 2021 has trended upwards, as estimated by all specialized agencies, on a par with the recovery of the world economy, overcoming the collapse that marked 2020.

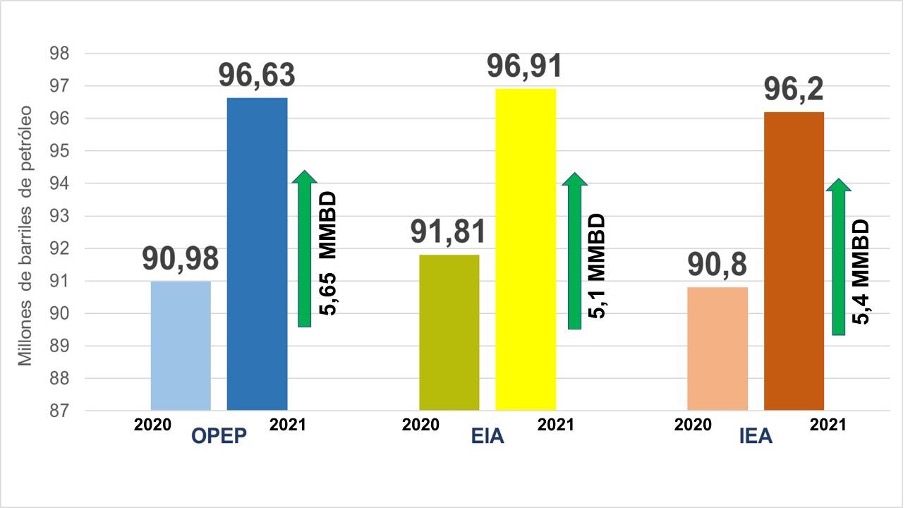

The agencies and institutions estimated that oil demand would be between 96.2 and 96.9 million barrels per day, an annual increase of between 5.1 and 5.6 million barrels per day, forecasting that the recovery would occur mainly in the 4th quarter of the year, while the recovery of the world economy stabilizes.

The progress of mass vaccinations against COVID-19 and the lifting of restrictions on internal and external mobility in countries, particularly in Europe, the US, and Asia, along with the recovery of trade, production, tourism, and employment, generated expectations and projections that pointed to an increase in world oil demand, toward the last quarter of the year above the forecasts made during the first half of 2021. Nonetheless, the slowdown in Asian economies, particularly China, due to energy supply problems, the inflationary phenomenon, the high costs of energy in Europe, together with the drop in demand in India and the emergence of the COVID-19 variant, Omicron, led to a downward adjustment of the initial demand projections for the last three months of 2021.

INITIAL DEMAND ESTIMATES

(January – December 2021)

OPEC’s Monthly Report for December forecasts that 2021 will end with a demand of 96.63 MMBD, an annual increase of 5.65 MMBD, which, however, is 250 MBD below the estimate for the first eight months of the year.

For its part, the IEA projected a global demand of 96.2 MMBD for 2021, an annual increase of 5.4 MMBD in global oil demand. Meanwhile, the EIA projected a year-end demand of 96.91 MMBD, an annual increase of 5.1 MMBD.

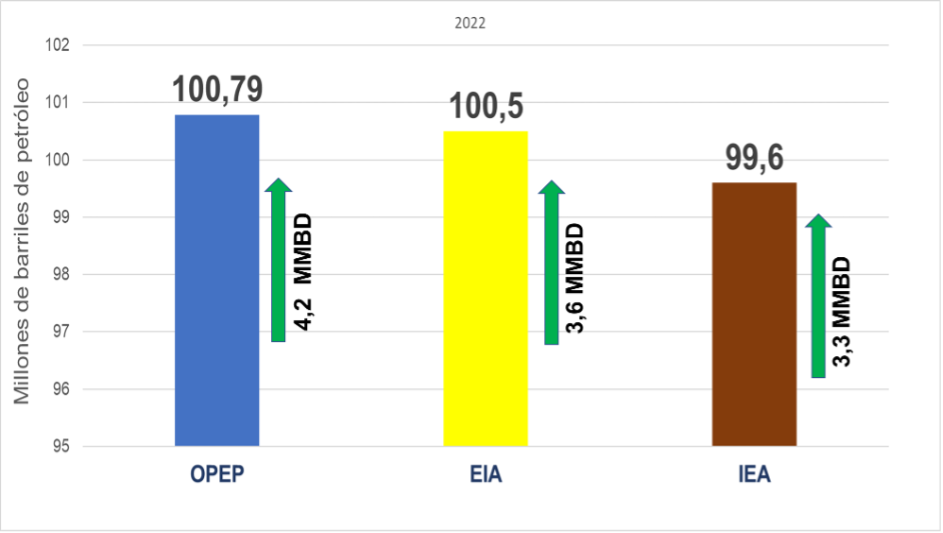

By 2022, given the growth projections in advanced and emerging economies, as well as the progress expected in the vaccination process -even with a third dose- all sources (OPEC, EIA, IEA) project a global demand close to or above 100 MMBD, returning to the levels of the last half of 2019, before the onset of the pandemic.

On its part, OPEC estimates in its December Report for 2022, a demand of 100.8 MMBD, with an annual increase of 4.2 MMBD. The EIA foresees a demand of 100.5 MMBD, with an annual growth of 3.6 MMBD; while the IEA, unlike the others, projects a demand of 99.5 MMBD for 2022, with an increase of 3.3 MMBD, which is closer to the growth forecast by the current US administration.

PROJECTED DEMAND 2022

STORAGE

The level of crude oil and product inventories is a determining factor in measuring the stability of the oil market. Throughout 2020, due to the collapse of the demand and the oversupply of oil in the market, inventories reached historic levels, even above their storage capacities, which caused -for the first time in the centennial history of the oil industry- negative prices, such as those recorded on April 20 of last year, when WTI traded at -$37 per barrel, due to the collapse of Cushing Oklahoma.

In 2021, as a result of OPEC+ production cuts and the recovery of demand, excess inventories were drained, returning them to their average levels of the last 5 years. This achievement in stabilizing the market has been one of the most important ones reached by OPEC+ in its efforts to stabilize the oil market.

In OECD countries, inventory levels are below the record levels reached in 2020 and below the average in the 2015-2019 period, higher than the increase in oil product storage in the same period. According to OPEC’s December MOMR, OECD countries’ commercial inventories of crude oil and products stood at 2.773 billion barrels in October, falling by 356 million barrels from the same period in 2020 and 174 million barrels below the 2015-2019 average. As for days of inventory coverage, in October it was 61.7 days, 12.1 days lower than in October 2020.

In its latest monthly report, the EIA estimated total crude oil and oil product inventories in OECD countries at 2.784 million barrels for October, a monthly drop of 1.3 million barrels, after a monthly fall of 22.7 million barrels in September.

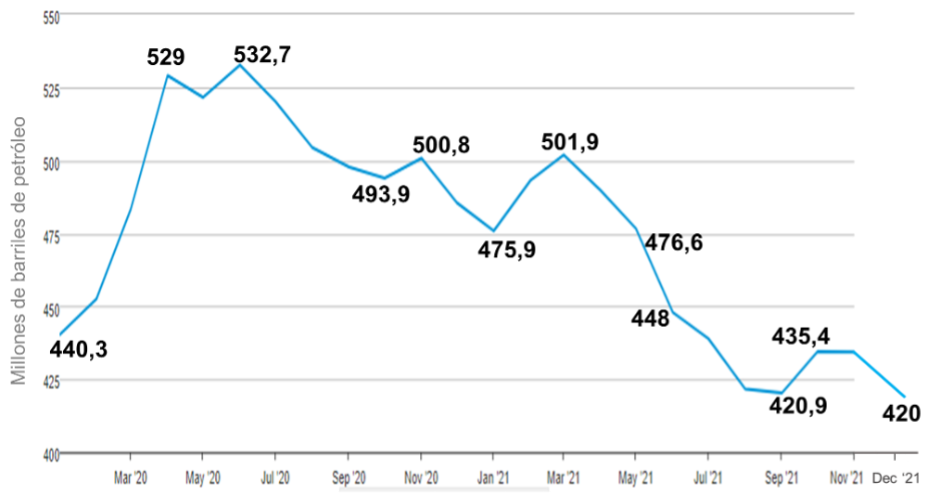

At year-end, US crude oil inventories closed at 1.8 billion barrels, of which 423.6 million correspond to commercial oil inventories and 596.4 million to strategic reserves, the latter with a drain of 41 million barrels in 2021, of which 25 million did so since September of this year. The latest EIA weekly report, on December 29, shows that at the close of the week of December 24, commercial and strategic oil stocks had a weekly fall of 3.6 and 1.35 million barrels, respectively, with a drain of 12.3 and 5.84 million barrels since December 3, standing at 420 and 595 million barrels. These have not stopped falling since September 10 and have drained 26.3 million barrels, dropping below 600 million barrels for the first time in more than 18 years.

U.S. COMMERCIAL CRUDE OIL INVENTORIES

(January 2020 – December 24, 2021)

The trend of US commercial crude oil inventories in 2021 continues to be estimated downward, adjusting the year-end projection to 426.2 million barrels, 5.6 million barrels lower than the projection estimated in November. By December 24, coverage days dropped to 26.7 days in the week, while they had been at 28.3 on November 19.

By 2022, EIA projections estimate that as US oil production consolidates and increases above 11.5 MMBD, commercial crude oil and oil by-product inventories and strategic oil reserves will continue to drain, this time by 82.7 MMBD, to close the year at 1.72 billion barrels (1.27 billion in commercial inventories), where strategic crude oil reserves will fall by 47.5 MMBD, to close 2022 at 548.9 MMBD; and commercial oil inventories will rise by 17.4 million barrels, to 441 million barrels at the end of the year.

As for the OECD countries, the same EIA estimates that commercial inventories of crude oil and oil by-products will increase by 112 million barrels, to end the year with 2.86 billion barrels — all of this in a year in which the US decided to release 50 million barrels of oil from its strategic oil reserves, while India announced that it will do the same with 5 million barrels and the UK with 1.5 million barrels.

VENEZUELA

ASSESSMENT

In the context of the deep economic, political, and social crisis that has affected the country since 2015, the Venezuelan oil industry continues to be submerged in the worst crisis of its centennial history, where the entire sector looks dysfunctional, mainly due to the collapse of the operational and management capacities of PDVSA.

Beyond the speeches, propaganda on social networks, and the government’s repeated promises, the reality is that the indicators by which the oil industry’s management can be measured, namely oil and gas production, exports, refining, supply to the domestic fuel market, and oil revenue collection, are all down and at the lowest levels in its history, a 90-year setback in the sector’s capabilities.

The collapse of the oil industry has deprived Venezuela -an oil country par excellence- of the oil income that, until 2013, represented 96% of the country’s foreign exchange earnings, which has been the fundamental origin of the terrible economic crisis in which the country has been plunged since the beginning of 2015. Since 2017, after the raids, imprisonments, and persecution against hundreds of PDVSA managers and workers, the government appointed the National Guard General Manuel Quevedo, as head of PDVSA, and placed on the Board of Directors of the company political operators of the government, militarizing the company at all levels and stripping it of its technical capabilities and management knowledge. Between 2016 and 2021, more than 30,000 qualified and specialized workers have left PDVSA.

From that point on, the government began a process of dismantling the Full Oil Sovereignty Policy that governed the sector between 2004 and 2014, after the defeat of the Oil Sabotage of 2002-2003 and the refounding of PDVSA, handing over the management and control of the oil sector to private and transnational operators, privatizing and handing over the company’s assets, as well as the management of production and exports to private interests, all to no avail.

The privatization of PDVSA and the delivery of oil have been a disaster. Nowadays, oil production as of November stands at 625 MBD, for an annual average of 539 MBD, while the country continues to suffer a chronic shortage of fuels, gasoline, diesel, and gas.

It is always important to remember that during the period of Full Oil Sovereignty, between 2004 and 2014, $700 billion in revenues entered the country from oil exports, leveraged by an average production of 3 million barrels per day, exports of 2.5 million barrels per day, and a supply of 600,000 barrels per day of fuels – gasoline, diesel, and gas – to the domestic market. Thanks to these revenues, the country was able to sustain the massive social development programs known as Missions: Educational Missions (Robinson, Ribas, and Sucre), Health Missions (Barrio Adentro, Misión Milagro), Food Missions (Mercal, PDVAL, Casas de Alimentación), and Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela, which built between 2010 and 2013 600,000 real homes; among other programs that allowed the country to achieve the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, as well as the development of large infrastructure and industrial, manufacturing, and agricultural projects that allowed the country to sustain its development, which maintained an economic and social growth for ten continuous years, with a GDP of $300 billion, an average inflation rate of 25%, a monthly minimum wage of $450, and international reserves of $45 billion.

At the same time, PDVSA, our national company, ranked in 2013 by the Petroleum Weekly Report as the 5th oil company worldwide, had 100,000 workers, $231 billion in assets, $129 billion in plants and equipment, $84.486 billion in equity, a production of 3 million barrels per day, 2.4 million barrels of exports, 1.2 million barrels processed in our national refining circuit to meet our domestic consumption and export needs, as well as annual revenues of $134 billion per year (all these numbers audited by KPMG and reported openly to the country) [34].

This was the company that we handed over back in August 2014, PDVSA, a powerful national company with full technical, financial, and management capabilities; a popular and revolutionary company, at the service of the country and national operator, subordinated to the state and the Full Oil Sovereignty Policy.

THE DELIVERY OF THE OIL AND

PRIVATIZATION OF PDVSA

Between 2015-2017, the government, with absolute control of PDVSA’s Board of Directors, took control of all the company’s resources and funds, including resources from its operational budgets, and workers’ funds for other purposes and priorities, suspending hiring processes, supplies of parts and equipment, as well as plant shutdowns and maintenance of facilities.

The government, greedy for resources and without any understanding or interest in the operations of the company, diverted the resources and indebted PDVSA with an increase of the Chinese Fund of $30 billion. It also used CITGO as a funding source for the government, whose policy was to go further into debt in order to prioritize the payment of the debt with international creditors. As stated by maduro himself, between 2013 and 2017, more than $70 billion of debt were paid while the country was deprived of the imports necessary for its operation and PDVSA of its operating resources, as denounced by Eulogio Del Pino, former president of PDVSA, a day before his arrest in a video posted in social media [35].

Since 2018, and after the militarization of the company, PDVSA’s management has been characterized for being anti-popular and anti-worker. During General Quevedo’s administration, all social development programs and missions supported by PDVSA were suspended, including such sensitive programs as the bone marrow transplant program for children with cancer. Furthermore, the social benefits and labor conquests of the workers of the Ministry of Oil and PDVSA were taken away and canceled, including their savings and pension funds, their medical insurance, and other social benefits. The government acted in PDVSA with absolute disregard for its workers, imposing an atmosphere of persecution and fear, using security forces and proto-fascist groups hired for this purpose and included in the company’s payroll.

From then on, and in line with the economic package [36] announced by maduro in August 2018, the government, in blatant violation of the Organic Law of Hydrocarbons [37]in force, began to relinquish, through Decree 3.368[38] the oil production areas under PDVSA’s control to private operators, under the illegal figure of «oil services contracts», and also handing PDVSA’s participation in the Orinoco Oil Belt over to Chinese and Russian transnationals, ceding the control of the operations and the control of oil exports. Using the Supreme Court of Justice and sentence [39] number 156 of March 21, 2017, the government has yielded important production areas, new and existing, to briefcase companies without any experience and capital, to pay political favors, to the detriment of the possibilities of increasing oil production in the country.

The government eliminated the sale of oil using the price formula and the control of exports by closing the office of the Ministry of Oil in Vienna and re-editing the old policy of oil discounts. Venezuelan oil is sold by private companies with massive discounts of more than 40%.

In the international arena, both PDVSA and the government have ignored the development of the international arbitration trials, which have allowed both Conoco Phillips and the briefcase company, Crystalex, to take control of the company’s assets abroad and to obtain favorable judicial decisions for the control of CITGO and for the payment of $11 billion -a decision on which the Venezuelan Government has not yet objected. All this has happened amid absolute negligence of both the company and the government to defend the assets of the Republic abroad.

Again, it is important to remember that, until 2014, with the Political-Legal team of the Ministry of Oil and our international lawyers, we faced and won the lawsuits before the ICSID and the ICC brought by Exxon Mobil and Conoco Phillips against PDVSA and the Republic.

On the other hand, the Venezuelan Government and the Foreign Ministry have ignored the advance of Exxon Mobil and the other transnationals, Hess Corporation (USA) and China National Offshore Oil Corporation CNOCC (China), in the waters of the Essequibo, despite the irrefutable reality that there is a legitimate territorial dispute over this area.

Given the silence of the Venezuelan Government, Guyana is today emerging as the new South American oil province with a current production of 120 MBD of oil in the waters of the Essequibo, with plans to increase 350 MBD in 2022 and up to 750 MBD by 2025.

The Venezuelan Government has been negligent in the handling of a territorial dispute with a neighboring country, inaction that has been used to mark territory and advance in the dispossession of the resources contained in the aforementioned zone, which could be part of the patrimony of all Venezuelans.

PDVSA’s last intervening board, the ARA Commission, assumed control of the oil sector in February 2020, to advance a governmental plan for the sale and relinquishing of PDVSA’s assets and oil areas, in contravention of the Organic Law of Hydrocarbons and the Constitution. In order to advance its plans, the ARA Commission has counted on the approval of the Anti-Blockade Law [40], an unconstitutional law that intends to hand over State and national assets in a SECRET manner to private and transnational operators.

By means of an absolutely opaque and illegal management, the government has been handing over infrastructure, assets, equipment, and oil fields to private operators; all of this with no regard for the mechanisms of control and accountability of public affairs established in the laws of the Republic.

Despite the government’s desperate attempts to attract transnational capital to the sector, the remaining international oil companies in Venezuela, such as Rosneft, Total, Equinor, and Aipex, have left the country, even surrendering their assets and declaring them as losses.

There is no legal framework or legal security to participate in the oil business, while PDVSA has neither qualified personnel nor the management or plan to recover production and sustain the oil activity.

The service sector, essential to the oil activity, is decimated. The companies receive payment for their services in paper bags filled with cash, after paying the innumerable commission agents and intermediaries of the government and the company that meddle in their business or activities, always under the threat or fear of legal action that will take away their business or even their freedom.

The dysfunctionality and decomposition of the government and PDVSA at all levels scare off investors and oil operators, who, in many cases, are not willing to be involved in illicit operations. Their departure from the country is a clear sign of the government’s failure, even in the management of its illegal plans to hand over the oil industry.

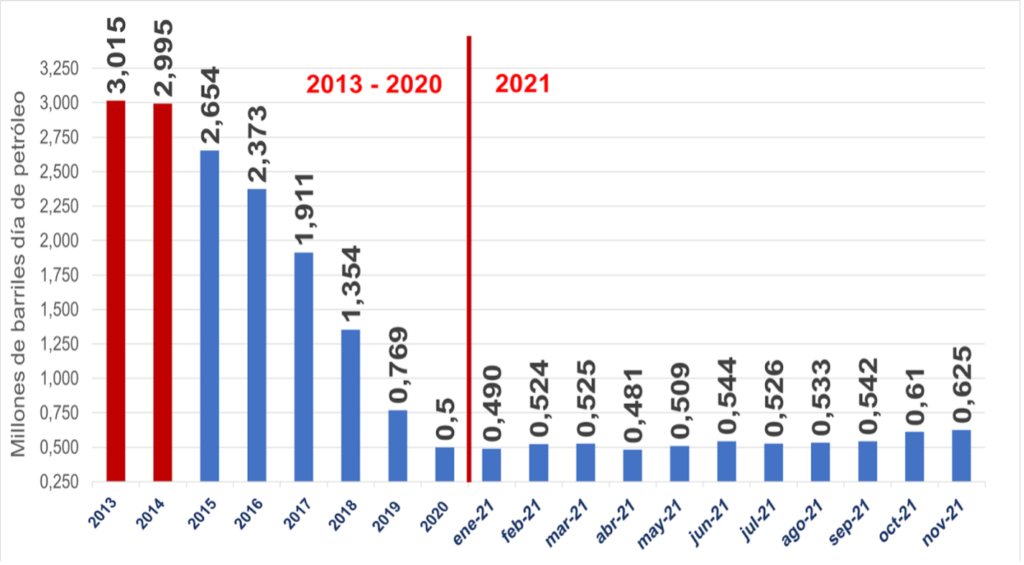

PRODUCTION

According to OPEC’s December Market Monitoring Report (MOMR), Venezuela’s oil production for November stood at 625 thousand barrels per day (MBD), which yields an annual average — without December production — of 539 MBD. This average year’s production is only 39 MBD above the 2020 average production (the worst year in the world oil industry) and 257 MBD still below the 2019 average production of 796 MBD.

VENEZUELA OIL PRODUCTION

(2019-2020-November 2021)

The average production for the year of 539 MBD is 2,472 million barrels below our 2013 average production. In other words, between 2014 and 2021, Venezuela has lost 82% of its oil production capacity, despite having the largest oil reserves on the planet, certified at 316 billion barrels of oil. This constitutes an unprecedented case in the history of the oil industry worldwide.

PRODUCTION VENEZUELA

(2013, January 2020 – December 2021)

Venezuela’s current oil production levels are far from the promises [41] made at the beginning of the year by Oil Minister Tareck El Aissami and Nicolás Maduro himself, who promised to reach 1.5 million barrels by the end of the year, later adjusting the initial figure to 1 million barrels per day. This is the third time that the Venezuelan government has adjusted the country’s oil production downwards since Nicolás Maduro announced, in January 2020, that it would reach 2 million barrels by the end of that year.

The same happened with the minister’s promise that by the end of July the fuel shortages in the country would be solved and the long queues would end.

None of this has happened beyond the technical discussions of corrupt journalists and «experts» in our oil country. When oil goes bad, it is felt on the streets. If the government was able to recover the production and export of oil or fuel production, the change would be felt in the national economy and immediately show in the standard of living of the citizens, but, unfortunately, this is not the case.

There is political intentionality by some «experts», articles of certain agencies and media to show a «miracle» in the recovery of the country’s oil production, when it is counted within the production volumes, what is called the «operated production»; that is to say all the barrels extracted, including the barrels of water, as well as the diluent imported from Iran.

These articles, whose sources are internal reports manipulated and leaked by the government itself, seek to support the privatization policy of the sector, the modification of the Organic Law of Hydrocarbons, and to leave without effect the constitutional reservations regarding the oil issue.

The reality, despite the government’s unsuccessful propaganda campaign, is that in order to repair the damage caused by the disastrous oil management of the last 8 years and the collapse of the oil production in the country, political will to recover PDVSA and our sovereignty over the management of oil is necessary.

A political change in Miraflores is required; a national vision that allows us to resume the full oil sovereignty as a policy for the sector. It is necessary to reestablish the rights of the oil workers, free the kidnapped workers and managers, and put an end to fear and persecution. We need to provide the sector with political and technical leaders and patriotic management in PDVSA, with oil knowledge and political commitment to the country’s well-being.

A deep analysis of the current situation of our areas and fields will have to be made, taking into account the characteristics and ages of each one in order to establish a plan -something that the government does not have- to recover the industry, as we did after the defeat of the oil sabotage.

The plan to recover production in Zulia is not the same as in the North of Monagas or in the Orinoco Oil Belt. We need the knowledge of our best technicians and managers, of the oil services, of the committed workers. This cannot be left in the hands of adventurers and briefcase companies as has been the case up to now.

The efforts to recover our large Refining and Upgrader complexes require specific knowledge and technology, as well as reestablishing the best technical and operational practices.

The recovery of the oil industry and PDVSA is a complex task, but one that can be achieved in the medium and long term, with the participation of all the national forces and capacities, as well as international support, always under the correct political leadership of the Ministry of Oil and the operational strength of Petróleos de Venezuela.

It is not about posting tweets or creating the illusion that the oil industry will recover overnight. This, as we know, is simply not possible. The oil issue should be a matter of national discussion: show the figures, compare policies and results. This government has already had 8 years with all the power in its hands – including the absolute control of PDVSA – and the results have been disastrous.

The year 2021 closes with a recovery of the international oil industry, with a stable oil market, a sustained recovery of demand, and a higher price of oil, which everything indicates will remain above $80 per barrel.

Venezuela will continue to be an oil-producing country, with the largest reserves on the planet, and must make progress in resolving the serious political problems it faces in order to focus on the recovery of the oil industry and put the oil revenues at the disposal of the people and the reconstruction of the country, only in this way, with the sovereign management of oil, we will get out of the unprecedented crisis we are facing.

Bibliographic References

- [1] Press release, «Classification of SARS-CoV-2 variant omicron (B.1.1.529) as a variant of concern, World Health Organization WHO, 26 November 2021.

- [2] Jamie Smyth, «Moderna chief predicts existing vaccines will struggle with Omicron, Financial Times 30 November 2021.

- [3] Joe Biden, «President Biden Announces Release from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve As Part of Ongoing Efforts to Lower Prices and Address Lack of Supply Around the World, The White House, November 23, 2021.

- [4] 23rd OPEC and non-OPEC Ministerial Meeting, OPEC, December 2, 2021.

- [5] «Monthly Oil Market Report December 2021«, OPEC, December 13, 2021.

- [6] «Oil Market Report – December 2021«, International Energy Agency IEA, December 13, 2021.

- [7] «Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University, December 29, 2021.

- [8] Yousef Gamal El-Din, «Saudi Energy Minister: Oil Rebound Can’t Be Taken For Granted, Bloomberg TV, October 24, 2021.

- [9] Press Release, «Joint Ministerial Statement, The Eighteenth ASEAN+3 (China, Japan, and Korea) Ministers on , Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industries of Japan, September 16, 2021.

- [10] Editor, «EU passes first chunk of green investment rules, gas and nuclear still to come, Euractiv, December 9, 2021.

- [11] Storage Data«, Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE), December 29, 2021.

- [12]Press Release, «Certification procedure for Nord Stream 2 suspended, Bundesnetzagentur, November 16, 2021.

- [13] Editor, «Scholz warns of «consequences» over Russian-German gas pipeline if Russia invades Ukraine, Deutsche Welle, December 08, 2021.

- [14] Editor, «Russia ready to take measures if NATO expands to its borders, Putin warns, TASS, December 21, 2021.

- [15] Monthly Oil Market Report December 2021«, OPEC, December 13, 2021.

- [16] «Short-Term Energy Outlook Data Browser,» U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), December 7, 2021. (EIA), December 7, 2021.

- [17] «Weekly Supply Estimates,» U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), December 29, 2021. (EIA), December 29, 2021.

- [18] Joe Biden, President Biden Announces Release from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve As Part of Ongoing Efforts to Lower Prices and Address Lack of Supply Around the World, The White House, November 23, 2021.

- [19] «The Paris Agreement«, UN Climate Change Convention, 2005.

- [20] Joe Biden, «The Biden Plan For A Clean Energy Revolution And Environmental Justice,» Joe Biden, October 2020.

- [21] Press Room, «Gulf of Mexico Lease Sale Results Announced, BOEM Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, November 17, 2021.

- [22] Samuel Chamberlain, «Federal judge blocks Biden moratorium on new oil, gas leases, New York Post, June 15, 2021.

- [23] Communiqué, «EO 14008: Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), January 27, 2021. (DOE), January 27, 2021.

- [24] WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK REPORTS, International Monetary Fund IMF, October 2021.

- [25] OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 2, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD, December 1, 2021.

- [26] Latin America and the Caribbean will grow 5.9% in 2021, reflecting a statistical drag that moderates to 2.9% in 2022, ECLAC, August 31, 2021.

- [27] World Economic Outlook, World Bank, June 2021.

- [28] «Consumer Price Index Summary,» U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 10, 2021.

- [29] «Annual inflation up to 4.9% in the euro area«, Eurostat, December 10, 2021.

- [30] Consumer Prices for November 2021,» National Bureau of Statistics of China, December 10, 2021.

- [31] Tobias Adrian and Gita Gopinath, «Addressing Inflation Pressures Amid an Enduring Pandemic,» International Monetary Fund, December 03, 2021.

- [32] Global recovery is strong but with imbalances, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD, December 1, 2021.

- [33] Debt transparency in developing economies, World Bank, November 11, 2021.

- [34] Executive Directorate of Budget and Control and the Corporate Management of Public Affairs, «Annual Management Report 2013«, PDVSA, January 2014.

- [35] Eulogio del Pino«, Twitter, November 30, 2021.

- [36] Editor, «Maduro announced a confusing economic package, Banking and Business, August 18, 2018.

- [37] «Ley Orgánica De Hidrocarburos«, Ministry of Petroleum of Venezuela, May 24, 2006.

- [38] Nicolás Maduro, Decree 3.668, Finanzas Digital, 12 April 2018.

- [39] Ruling No. 156 dated March 29, 2017, issued by the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice interpreting Article 33 of the Organic Hydrocarbons Law, Pandectas Digital, May 2017.

- [40] This is the Anti-Blocking Law with all its details, Banking and Business, September 30, 2020.

- [41] Editor, «Maduro decrees extension of the energy emergency in the entire oil industry for one year, Finanzas Digital, February 19, 2021.